Residential Care: Policy context

Derren Hayes

Tuesday, January 29, 2019

Sir Martin Narey's government-commissioned independent review of children's residential care in England has significantly shaped policy developments in the sector since being published in July 2016.

The report - Children's Residential Care in England - was widely supportive of the quality of children's home services and staff, but included 34 recommendations for how the system could be improved. Among these were proposals to improve the commissioning process, reduce the number of children placed in homes outside their local area, develop restorative approaches to tackle unacceptable behaviour, test new models of homes to help young people transition to independent living, and for children's services leaders to work together to reduce the cost of residential child care.

The government's response to the Narey review, published in December 2016, included policy initiatives to progress a number of the recommendations in Sir Martin's report. However, on the key assertion that local authorities should band together into "large consortia" to "obtain significant discounts" from private and voluntary sector providers in an attempt to get better value for money, it appears little headway has been made.

Demand and funding

The amount spent by councils on looked-after children is forecast to rise by 9.2 per cent in 2018/19 to £4.2bn, largely as a result of the increase in the number of children taken into care over recent years - up to a total of 75,420 in the year ending 2017/18. Since 2010/11, there has been a 78 per cent rise in children over the age of 16 taken into care - five-times higher than the overall rise of 15 per cent. These children tend to have more complex needs making them harder to place with foster carers and more likely to go into children's homes.

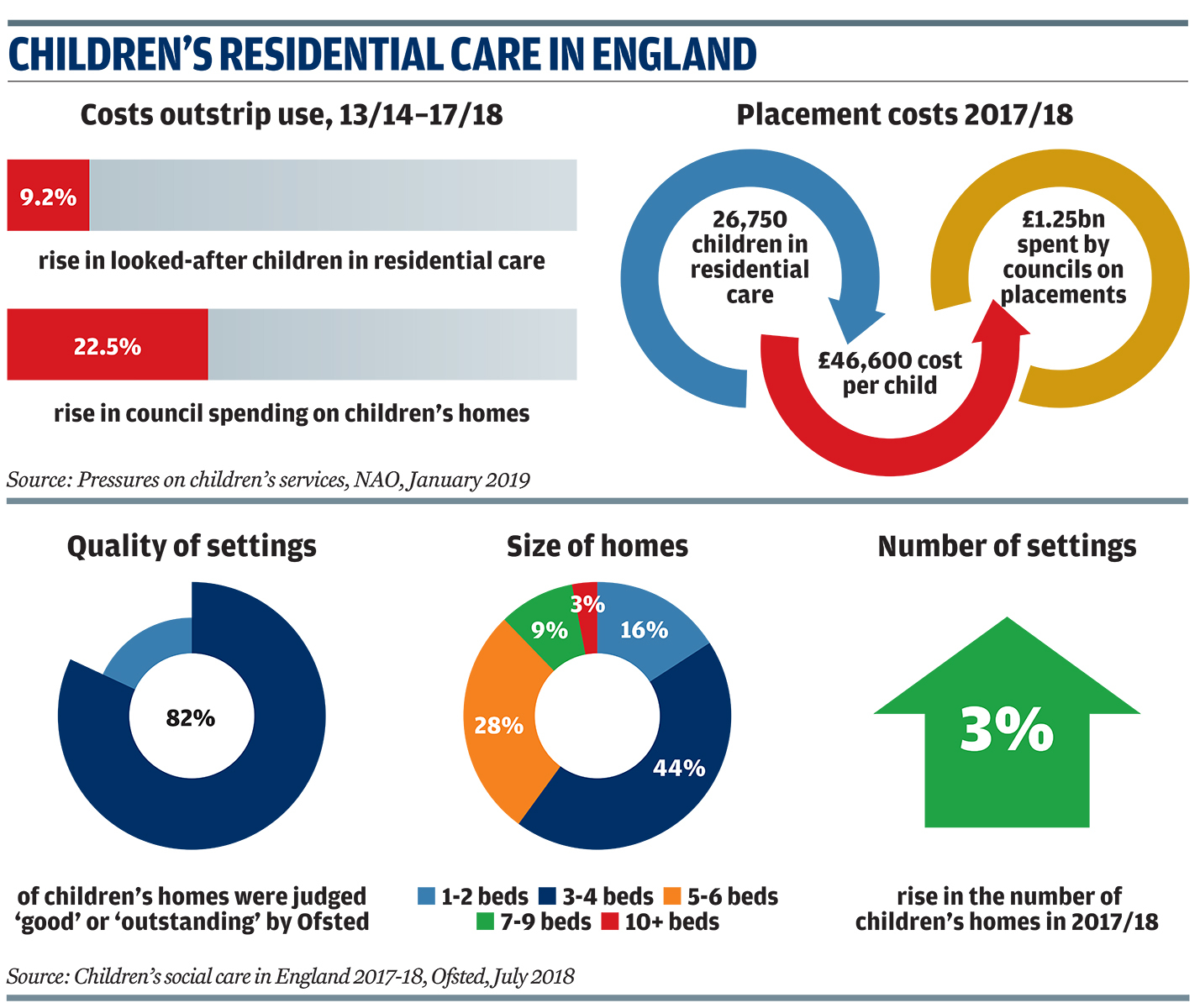

The number of children placed in residential care rose 9.2 per cent between 2013/14 and 2017/18. However, over the same period, the amount spent by councils on such placements was up 22.5 per cent to £1.25bn, according to a National Audit Office (NAO) report. The analysis shows the average spend on a residential care placement was £46,600 per child, more than twice the amount of a foster care placement.

The NAO found the majority of local authorities reported having insufficient residential child care capacity available to meet demand for children aged 14 to 17.

Latest Department for Education statistics show 11 per cent (8,296) of all looked-after children were living in a children's home, semi-independent accommodation or secure unit on 31 March 2018. Half of these placements are within 20 miles of their home, compared with 79 per cent for foster placements.

Provider market

Ofsted's Children's Social Care in England report published last year shows there were 2,209 residential child care settings registered with the inspectorate at 31 March 2018, three per cent higher than the year before. This growth is due to a rise in privately-run homes, up from 1,481 to 1,561 over the year, which now account for 73 per cent of the entire residential child care market. The number of voluntary sector settings remained around the same while those run by local authorities continued their downward trend of recent years, declining three per cent to 423.

At 31 March 2018, there were 44 councils in England that did not run any children's home in their area. Despite the falling national numbers, over the course of the year six authorities increased the number of homes they ran.

In terms of size of homes, 44 per cent of settings offer three and four beds, with five and six beds accounting for 28 per cent. Homes of 10 or more beds account for just three per cent of all settings, most situated in London and the South East.

Although the number of children's homes increased, the number of places changed by less than one per cent (from 11,664 to 11,746). This smaller increase is because of the drop in the number of places in residential special schools registered as children's homes.

The Ofsted data shows the quality of children's homes remained roughly the same as last year. Of the 2,112 children's homes of all types inspected in 2017/18, 17 per cent improved compared to 20 per cent the year before, while 21 per cent declined compared to 20 per cent in 2016/17.

Of the 2,120 children's homes that received a full inspection last year, 17 per cent were "outstanding", down one per cent; 65 per cent "good", up two per cent; 17 per cent "requires improvement", the same as the year before; and two per cent "inadequate", up one per cent.

Workforce issues

That 82 per cent of children's homes have been judged good or outstanding by Ofsted is recognition of the high standards of care provided by staff in the vast majority of settings. In his 2016 review, Sir Martin Narey praised the contribution of children's home staff highlighting how their achievements are sometimes "dismissed, not because of what they achieve but because of the modesty of their qualifications".

Sir Martin warned against England following the Scottish policy of requiring all children's home staff to be graduates, and instead called for the residential child care workforce to have access to continuing professional development and team-based training courses, such as the RESuLT programme (see Research Evidence). He also called on the DfE to consider how more social worker students can spend time in children's homes during their practice placements, and for children's home managers to hold a social work qualification. The government is yet to take these forward.

In its response to the Narey review, the government said it would commission and disseminate qualitative research on best practice on recruiting staff, but has not yet done so. The Independent Children's Homes Association (ICHA) is also looking to undertake a similar project.

Since January 2015, staff working in children's homes in England have been required to obtain the Level 3 Diploma for Residential Child Care, with managers required to hold the Level 5 diploma. Research by NCB and TNS found that children's home staff were broadly supportive of the Level 3 diploma and Sir Martin concluded that it provided an "adequate baseline qualification".

Meanwhile, research by Kantar Public published last year found the Level 5 diploma had provided a clearer framework for managers compared to the previous National Minimum Standards (see Research Evidence).

Despite this positive picture, the Narey review highlighted providers' concerns about the recruitment and retention difficulties, partly due to low rates of staff pay. A recent development that has added to their concerns has been the legal case brought by staff in a residential home for disabled people against the Royal Mencap Society and which has potential implications for children's home providers. Last summer, the Court of Appeal overturned an earlier decision that residential care providers are liable to pay staff for "sleep-in" periods when working night shifts. However, Unison has lodged an appeal against the decision with the Supreme Court, and last year ICHA warned the uncertainty was harming staff morale and retention.

Emerging trends

A key recommendation of the Narey review was for the creation of an intermediate residential care option that helped young people make the transition from children's home to living independently. In its response to the review, the government announced it would trial so-called Staying Close arrangements to test out different approaches. In total, eight pilots have been launched, including one run by Fair Ways Foundation in Southampton (see practice example).

Staying Close involves offering young people leaving residential care the chance to move into nearby supported accommodation potentially up until they turn 21, in order to maintain attachments with their former home and to help them gain the skills needed to live on their own.

The pilots run until next year and are being overseen by the Residential Care Leadership Board, which was set up by the government to deliver the Narey review recommendations, and is chaired by former Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS) president Sir Alan Wood. Staying Close is one of the board's two priority areas until its long-term future is decided - the DfE is still considering whether to pursue a recommendation in the Fostering Stocktake to create an overarching "permanence board" to co-ordinate policy on all forms of care.

The other priority area for the leadership board is improving placement commissioning, an area that came in for criticism from Narey. He called for improvements in local and regional commissioning skills, and for the DfE to fund new approaches to delivering residential child care. To that end, the board is taking forward three projects to improve commissioning funded through the £200m Children's Social Care Innovation programme.

Scrutiny of residential child care placements is also set to increase as a result of recent policy developments. The government has established a National Stability Forum for Children's Social Care to be chaired by the DfE director general, the most senior civil servant with responsibility for children's social care, to bring leaders together to develop and share good practice. A key issue to address is the large number of children placed in residential care homes outside their council area. Official figures obtained by Labour MP for Stockport Ann Coffey showed that 61 per cent of children are now placed in homes "out of area", with that number rising 64 per cent between 2012 and 2017.

Linked to concerns about out-of-area placements, is the vulnerability of young people in children's homes to being targeted by gangs with the intension of exploiting them criminally or sexually. Children being placed far away from family and friends' networks is thought to be a key factor in the high rates of "missing" incidents of children in residential care.

Dealing with missing incidents and conflict between children's home staff and residents are major problems for the police, and is one of the reasons the government has launched a national protocol to reduce prosecutions of children in care. The protocol is based on a number of successful local initiatives, such as that developed by Dorset Combined Youth Offending Service (see practice example).

The rising costs of residential child care has led to concerns being raised about excessive profits made by private providers and for some to question whether the profit motive should be removed entirely from the care sector (see ADCS expert view, below). However, provider organisations highlight their rising costs - Ofsted registration fees are set to rise by 10 per cent from April for the tenth year in a row, while staff costs have also risen. In fact, ICHA recently warned that one in 10 providers were facing closure due to rising costs and flat income levels (see provider expert view, below).

There is also the fact that children in care homes tend to have the most entrenched problems requiring the most therapeutic support. A national pilot of assessments for mental health problems for children when they enter residential care is yet to begin, but many homes have already developed their own specialism in this area (see Cove Care practice example).

Balancing the need for high-quality specialist care that gets good outcomes for children at a price that makes residential care cost effective for commissioners and providers is likely to remain a tough challenge in the years ahead.

ADCS VIEW

‘PROFOUND CHANGE' IN RESIDENTIAL CHILD CARE

By Stuart Gallimore, president of the Association of Directors of Children's Services and director of children's services, East Sussex Council

Children's homes do not get enough recognition for the vital work that they do, and, while it is true that the majority of the 75,000 children and young people in our care live with foster carers, or their extended family, for 6,000 or so of this number a residential placement really is the best fit. This can help children to regulate their own risk-taking behaviour by offering them valuable time and space to address earlier trauma or their difficulties in making attachments as part of a long-term care plan.

The best homes share some key features: a stable and dedicated team of staff led by an experienced registered manager; the relationships between children and staff are trusting and respectful; and, staff work in partnership with social workers and other professionals to provide stability and improve children's outcomes. This work is demanding but it is also rewarding. The complex and often overlapping health and social care needs of children in residential placements underlines the need for staff to be trained to a high minimum standard, equipped with specialist skills and have support in place to build their resilience.

In some countries residential care is provided by qualified psychologists, I'm not sure that's needed here, to my mind it's more important that staff consistently stick with a child through thick and thin, recognising the impact that bereavement or neglect can have on behavioural presentation. A move to improve the status of the children's residential sector and everyone working in this field is long overdue. The introduction of new children's home regulations and standards a few years ago attempted to do this but the government's skills targets have not yet been met, with only half of staff holding at least a level three qualification (equivalent to an A-level) in 2017/18, according to recent Ofsted data.

Hot on the heels of the news that a multi-million pound merger between two large social care providers is being investigated by the competition watchdog, Ofsted's latest annual report offered a fascinating insight into a sector that is in the midst of a profound change. There were 77 new children's homes opened in the last year, the majority brought forward by large providers. The total number of children's homes in England is at a record high yet the proportion of local authority-owned children's homes fell further still and almost a third no longer own any homes at all.

This new reality underlines the importance of effective strategic commissioning in order to help children to lead happy and successful lives. A placement shouldn't be treated as a positive outcome in itself. We need to be clear about the progress and impact we expect and manage performance in this regard. We no longer hold the levers of power in the sense of running our own homes but we shouldn't accept anything less than the best for the children in our care. I also wonder if the time hasn't come to begin to address the for-profit motive in providing care for our children?

PROVIDER VIEW

COLLABORATION CAN DELIVER INVESTMENT IN RESIDENTIAL CARE

By Jonathan Stanley, chief executive, Independent Children's Homes Association

In the first months of 2019 there are signs of growing appreciation for residential care for children. Sir Alan Wood tweeted that "more celebration is needed" over the fact that 82 per cent of homes are "good" or "outstanding", and that 97 per cent of homes meet the quality standards. The One Show broadcast to prime time viewing a quarter of an hour of positive coverage of children's homes.

Public and professional perception sees children's homes transform lives. How do we nurture these green shoots? It is the commitment to making constructive comment and contribution that must be assured. We need to reframe what might be a negative intent to result in positive exploration.

Rarely have I heard residential care referred to as ‘intensive', more commonly it is named as ‘expensive'. More expensive than what? Are the comparisons that lie beneath such comments accurate? What is the evidence?

The recent National Audit Office (NAO) report on children's services spotlights that residential care needs strategic planning and investment.

Children's homes have been experiencing a volatility of conditions. The sector requires stability. Children require stability. The two are connected. For children's homes to offer a secure base to children they also need to operate within an environment that provides stability. Stability connects child care and financial good practice.

We need all homes to be working in a financial, emotional, professional environment where all feel a belonging, so that everyone works in a focused child-led way.

The sector is working to high levels of occupancy - providers get 500-700 referrals a month. The NAO reported that demand is outstripping supply. The situation where providers were in competition for placements has reversed and it is local authorities who are in competition for the scarce number of placements. On any one day, potentially, there could be only between 75-125 placements available, and subject to the matching of needs to provision.

Experts have projected that to meet demand 125 homes may need to be opened. How has it got to this situation? How is it that investment - whether by local authorities, voluntary organisations or private sources - is now unattractive? If every home takes £1m to open, where does the investment come from?

There is a question as to whether the staffing for another 125 homes can be sourced. Already registered managers are in high demand. There needs to be investment in skilled staffing and this requires business planning.

Inside and outside homes this a time to be constructive and creative, two foundations of residential child care practice. Supportive, solution-focused engagement is welcome; leave any negativity at the door.

FURTHER READING

Pressures on Children's Social Care, National Audit Office, January 2019

Children looked-after in England and Wales 2017/18, DfE, November 2018

Children's Social Care in England 2017/18, Ofsted, July 2018

Children's Home Research: The Impact of Standards on Staff, Kantar Public, March 2018

Government Response to Martin Narey's Independent Review of Residential Care, DfE, December 2016

Children's Residential Care in England, DfE, July 2016

Click here to read more in CYP Now's Residential Care special report